At some point in our lives or another, all of us may have encountered a diverse array of children with unique needs beyond the conventional. Some of these children may demonstrate deficits in social communication and interactions, while others may find solace in the comfort of routine and may perform some repetitive or restricted behaviors. These individuals may be susceptible to sensory stimuli, as well as engage in self-stimulation (aka “stimming”) which are repetitive body movements that can help them manage their emotions. All of these attributes come together to form the umbrella known as “Autism Spectrum Disorder” (ASD).

Join us on this journey as we uncover the intricacies of Autism Spectrum Disorder, presented by the best mental health center in India.

-

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

To answer this question, Autism Spectrum Disorder (we will be using the short form, ‘ASD’), is a neurodevelopmental condition that encompasses a broad spectrum of challenging behaviours. These behaviours can include impairments in social communication and language development, and difficulties in perceptual and motor development. (Hooley et al., 2017).

The ASD symptoms typically appear in early childhood, and although it is a lifelong diagnosis, early intervention enables these individuals to lead productive, inclusive, and fulfilling lives. Many children having ASD excel in school, pursue higher education, find employment in adulthood, and engage in enjoyable activities. Although ASD is an intricate disorder and may be difficult for parents, peers, and even professionals to comprehend, our understanding of autism as a concept has significantly progressed, providing valuable insights that influence how we define, diagnose, and treat this disorder. (Hooley et al., 2017).

-

Why is Autism on a Spectrum?

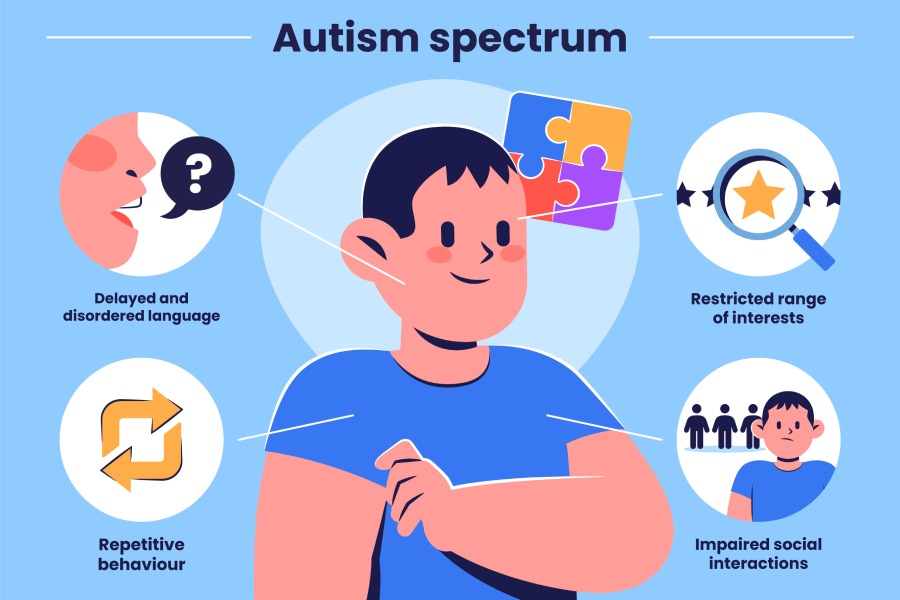

Autism is a heterogeneous condition – no two individuals with autism have the exact same characteristics. However, the difficulties manifested through autism fall into core domains that are reliably measured and usually consistent over time. (Lord, Cook, Leventhal & Amaral, 2000). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) has defined ASD based on two core domains – persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, and engaging in restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, activities, or interests. The spectrum nature of this condition becomes evident as these core features can vary significantly in their expression and intensity between individuals. Thus autism is referred to as a ‘spectrum’ as it recognizes a wide range of variations in strengths, challenges, communication patterns, and other characteristics that can vary greatly with individuals.

An ASD diagnosis is characterized by diverse combinations and degrees of behavioural deficits and excesses, hence, the impact of ASD can place individuals on a continuum of severity and affect them in various ways. (Kodak & Bergmann, 2020; APA, 2013).

- Now let us take a look at the clinical features of ASD

As we’ve seen earlier, children diagnosed with ASD tend to exhibit a spectrum of impairments and capabilities. A distinctive indicator of ASD is a child appearing distant or aloof from others, even in the earliest stages of life (Hillman, et. al., 2007). For example, a baby might exhibit limited expressions of joy, or excitement, and may appear to be less attuned to emotional cues in their environment.

Some of these clinical features are (Hooley et al., 2017)

1. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts.

Individuals with ASD may frequently encounter challenges in understanding and employing non-verbal cues, maintaining eye contact, participating in reciprocal conversations, and difficulty in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, which may hamper their daily lives. For example, an individual with autism may struggle to interpret facial expressions or identify sarcasm in a conversation.

2. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following.

- Stereotypical or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech. For example, repetitive tapping of fingers, insistence on arranging objects in a specific order, echoing phrases (known as echolia), lining up toys or objects in a specific order, etc.

- Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior. For example, insistence on following the same routine, resistance to changes to familiar settings, or engaging in ritualizing behaviors such as repeating specific phrases or actions.

- Highly restricted, fixed interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus. For example, memorizing details about train schedules, or memorizing facts about a certain historical period, etc.

- Hyper or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment. For example, demonstrating hypersensitivity to loud noises or bright lights, or demonstrating a hyposensitivity to pain or temperature, etc.

3. Symptoms must be present in the early development (but may not fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

For example, in early childhood, a child with ASD may exhibit subtle social differences such as difficulty in maintaining eye contact or engaging in conversations. As this child becomes an adolescent, these challenges may be further amplified due to the increased social demands in school at that age.

4. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

For example, ASD may affect an individual’s ability to engage in social relationships, create difficulties in educational settings, lead to limitations in employment, hamper independent living, and affect their overall emotional well-being as well.

5. These disturbances are not better explained by an intellectual disability or global developmental delay.

Theory of Mind related to autism

The ‘theory of mind’ allows us to infer mental states (beliefs, desires, intentions, emotions, etc.) in other individuals. It means to understand that others may have perspectives different from one’s own. (Baron-Cohen, Hartley & Branthwaite, 1989).

We use the ‘theory of mind’ in everyday interactions to make inferences about the thoughts and feelings of others. For example, you find out that your friend has received some disappointing news, and that they might need some comforting to make them feel better.

However, not everyone can interpret each other’s actions and speech in terms of what people intend. Abnormality in understanding other people’s emotional states is not the only psychological feature of autism, but it appears to be a core and possibly a universal abnormality among such individuals. (Baron-Cohen et al., 1993b).

In typical development, by the age of 3 to 4 years, children develop first-order abilities, that is, a basic understanding of people’s mental states (Happé, 2015). A good example of this is pretend play. At about age 5 or 6, children acquire second-order abilities, meaning that they can think about another person’s thinking about a third person’s thoughts (Israel, Malatras & Nelson, 2021).

Children with autism often have some of the basic elements of theory of mind, but may encounter challenges in using it at a level that one would expect, given their potential cognitive capabilities in other domains.

This deficit can lead to difficulties in the classroom, monitoring one’s intentions, understanding metaphor, sarcasm, and irony, difficulty with social skills, and lead to various other challenges in daily life. (Baron-Cohen, Hartley & Branthwaite, 1989).

Managing Autism

The primary methods for managing ASD include behavioral, psychosocial, and educational approaches. These interventions are often intensive and they are initiated early in development. Pharmacological treatments also play a supporting role in managing ASD.

1. Behavioral Approaches

Behaviorally based treatments are widely recognized as the most empirically supported interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder (Klinger & Dudley, 2019). These interventions are based on the principles of learning and the idea that behavior can be changed by altering the events that influence behavior. The behavioral interventions are tailored to the individual’s personality and personal needs and help them reduce challenging or maladaptive behavior and acquire adaptive behaviors.

According to Grogorenko et al., (2018), Behavioural interventions for ASD can be categorized into two main approaches

- Targeted approaches: These focus on specific areas, and address deficiencies such as language or social skills. They also address specific maladaptive behaviors, like stereotype behaviors or self-injury.

- Comprehensive approaches: These focus aim to address a broad range of primary and secondary issues that are associated with autism over an extended period of time. These also involve intensive and extended treatment.

(Israel, Malatras & Nelson, 2021).

2. Psychosocial Approaches

Social skills play an imperative role in a child’s ability to navigate their surroundings, and meaningfully interact with their environment and others. Children commonly begin displaying these social skills at a very young age, however, children diagnosed with ASD may require targeted interventions aimed at developing foundational social skills such as joint attention, social engagement, and social referencing. These deficits in social skills may strain relationships with peers and family, and thus early intervention is vital for developing these skills. (Kodak & Bergmann, 2020; Hansen & Carnett, 2018; Flynn & Healy, 2012).

The psychosocial approaches aim to enhance the social skills and emotional well-being of children and adolescents with ASD. Social skills training specifically addresses the difficulties associated with initiating and maintaining reciprocal social interactions. This training assists individuals in navigating through social situations, interpreting non-verbal cues, and fostering meaningful relationships. Social skills training has also been integrated into other approaches, and several specific practices such as video self-modeling and peer-mediated instruction, have demonstrated effectiveness in addressing skill deficits. (Wong et al., 2015).

Cognitive behavior therapy also helps address emotional regulation, executive functioning, and the management of anxiety or sensory sensitivities.

Psychosocial approaches strive to enhance overall adaptive functioning and quality of life by reinforcing the individual’s understanding and coping mechanisms in various emotional and social contexts.

(Israel, Malatras & Nelson, 2021).

3. Educational Approaches

The complete integration of students with ASD into mainstream classrooms has been a notable subject of discussion (de Boer & Pjil, 2016). Advocates voice that as children with ASD have different abilities, they require different classroom settings with special services dedicated and tailored to them.

The educational interventions strive to cultivate a structured and personalized learning environment for children with ASD. Some special education programs provide customized curricula that is designed to tackle the distinct learning styles and challenges associated with ASD.

Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), (Israel, Malatras & Nelson, 2021) can be used to support children with ASD in the educational setting. IEPs can help tailor educational goals, provide specialized instructional strategies, provide the appropriate accommodations and modifications, and include a system for regular monitoring and evaluation. Parental involvement is also encouraged in the planning of IEPs as they play a vital role in providing insights about their child’s strengths, challenges, and overall preferences (Wilczynski, Menousek, Hunter & Mugdal, 2007).

4. Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological Treatment primarily focuses on addressing the specific symptoms and associated conditions of ASD such as aggression, self-injury, agitation, and stereotypic behaviors. Although there is no medication that can treat the core symptoms of ASD, certain medications can be prescribed to manage the target problem behaviors of ASD.

These pharmacological treatments are frequently a part of a comprehensive treatment plan which includes behavioral, psychosocial, and educational strategies designed for the specific needs of each individual with ASD (Israel, Malatras & Nelson, 2021).

To conclude, Autism Spectrum Disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition that is characterized by a wide array of challenges in social communication, flexibility, and behavior. This forms a “spectrum” which acknowledges the individual differences in the presentation of symptoms, and the varying degrees of severity among individuals with ASD. Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder may also face complications in understanding the perspectives and points of view of others. Although there is no cure, behavioral, psychosocial, educational, and pharmacological approaches suggested by best child psychologists can be used to manage the symptoms of ASD and help individuals live a contented and fulfilling life.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5©). American Psychiatric Pub, Washington, DC (2013).

Baron-Cohen, S., Hartley, J., Branthwaite, A. (1989). Autism and “Theory of Mind.” Diagnosis and Treatment of Autism, 33-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0882-7_4

Baron-Cohen, S., Tager-Flusberg, H. & cohen, D. (eds) (1993b). Understanding Other Minds: perspectives from Autism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Boer, A., & Pijl, S. J. (2016). The acceptance and rejection of peers with ADHD and ASD in general secondary education. The Journal of Educational Research, 109, 325–332.

Hansen, S.G., Carnett, A. (2018). Defining early social communication skills: A Systematic Review And Analysis. Adv Neurodev Disord, 2 (1) (2018), pp. 116-128.

Flynn, L., Healy, O. (2012). A Review of Treatments for Deficits in Social Skills and Self-Help Skills in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord, 6 (1) (2012), pp. 431-441.

Happé, F. (2015). Autism as a neurodevelopmental disorder of mind-reading. Journal of the British Academy, 3, 197–209.

Hillman, J., Snyder, S., & Neubrander, J. (2007). Childhood autism: A clinician’s guide to early diagnosis and integrated treatment. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Hooley, J.M., Butcher, J, N., Nock, M., & Mineka, S. (2017). Abnormal Psychology, 17th Edition.

Israel, A. C., Malatras, J. W., Nelson, R. W (2021). Abnormal Child and Adolescent Psychology, Ninth Edition.

Klinger, L. G., & Dudley, K. M. (2019). Autism spectrum disorder. In M. J. Prinstein, E. A. Youngstrom, E. J. Mash, & R. A. Barkley (Eds.), Treatment of disorders in childhood and adolescence. NewYork: The Guilford Press.

Kodak, T., Bergmann, S. (2020). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Characteristics, Associated Behaviours, and Early Intervention. Pediatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 67, No. 3 (June 2020): 525-535.

Lord, C., Cook, E. H., Leventhal, B. L., Amaral, D. G. (2000). Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron, Vol. 28, 355-363, November, 2000.

Wilczynski, S.M., Menousek, K., Hunter, M. and Mudgal, D. (2007), Individualized education programs for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Psychol. Schs., 44: 653-666. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20255

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. A., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., et al. (2015). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1951–1966.”